The Republic of His Imagination:

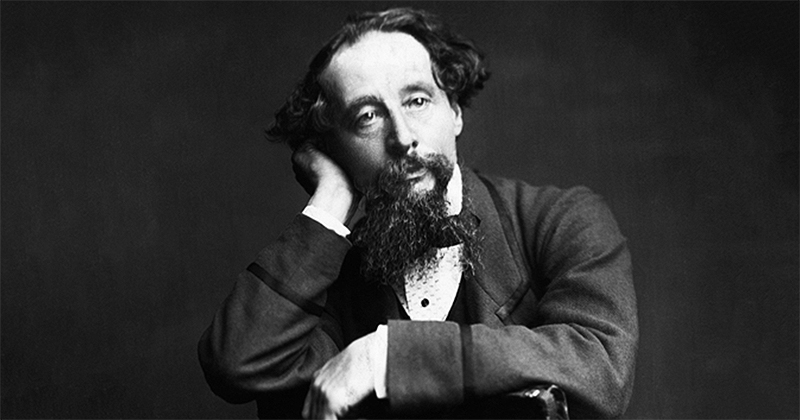

Charles Dickens in America

By Michael F. Bishop

Legend has it that in New York in 1841, as the ship delivering copies of the final installment of Charles Dickens’ The Old Curiosity Shop approached the pier, a vast crowd of impatient readers called to those aboard, “Is Little Nell dead?”

Dickens was the most famous novelist in the world and had seized the imagination of the American public.

“The Inimitable,” as Dickens had humorously christened himself, paid his first visit to the United States early the following year. He arrived in Boston eager to see for himself the young republic that had long fired his imagination. Only twenty-nine, he was rapturously welcomed by adoring fans and celebrated at “balls, dinners,” and “assemblies without end.” Overwhelmed, he told one audience that, “If I should live to grow old, the scenes of this and other evenings will shine as brightly to my dull eyes 50 years hence as now.”

But before long the adulation began to pall, and he tired of being mobbed everywhere he went. He complained to a friend, “I can do nothing that I want to do, go nowhere where I want to go, and see nothing that I want to see. If I turn into the street, I am followed by a multitude.”

He was also frustrated at America’s lack of copyright laws, which allowed unscrupulous publishers to print cheap editions of his novels from which he received no profit and declared himself “the greatest loser alive.” Beyond his understandable frustration at being commercially exploited, the pirating of his work added to his perception that America fostered a culture of greed.

Dickens visit to the nation’s capital did nothing to enhance his opinion. He dismissed Washington as “The City of Magnificent Distances,” with “Spacious avenues, that begin in nothing, and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that only want houses, roads and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament.”

He was particularly horrified by the ubiquitous habit of chewing tobacco, and the constant expectoration into spittoons or on the floor. He primly observed, “Washington may be called the head-quarters of tobacco-tinctured saliva. The thing itself is an exaggeration of nastiness, which cannot be outdone.” He was shocked to see that even in the White House, “tobacco-tinctured saliva” flew around with abandon. Waiting in an antechamber (today’s Treaty Room) for his appointment with President John Tyler, he observed that those around him “bestowed their favours so abundantly upon the carpet, that I take it for granted the Presidential housemaids have high wages.”

He witnessed a far worse practice in Baltimore, where at dinner he and his companions “were waited on, for the first time, by slaves. He felt “a sense of shame and self-reproach” for “exacting any service from human creatures who are bought and sold.” He would later condemn what he called the “atrocities” of slavery and the “the miserable aristocracy spawned of a false republic” that held men in chains.

All of this left him in low spirits. “I never knew what it was to feel disgust and contempt ‘till I travelled in America,” he wrote. “This is not the republic of my imagination.”

Upon his return to England, he poured his scorn for America into two literary works, the nonfiction American Notes for General Circulation and the novel Martin Chuzzlewit. Neither were particularly successful, and even his fondest American admirers expressed dismay at the harshness of the portrait he painted of their country.

A quarter century would pass before his second and final American visit in 1867. By then, the passions inflamed by his first visit had waned, and his dramatic readings “A Christmas Carol” and other works were hailed by an adoring public.

A New York newspaper observed, “Dickens’ second coming was needed to disperse every cloud and every doubt and to place his name undimmed in the silver sunshine of American admiration.” And there it remains.

Michael F. Bishop, a writer and historian, is the former executive director of the International Churchill Society and the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Commission.